Understanding Tritones & Chord Substitutions

Contents

Tritones definitely add spice to your playing. But, many people are confused when it comes to using them. In this article, I am going to explain:

- The Tritone

- What is Resolution?

- Dominant Motion (Resolution)

- ii-V-I's

- Using Tritones in ii-V-I's

The tritone is an interval. An interval is a distance between two points. We measure distance on the piano in intervals. A tritone is the distance between the root and the #4. So, C to F# is a tritone.

Years ago you could get banned from the church for even playing a tritone due to its very "harsh" or dissonant sound. It used to be called the "devil's interval".

Ironically, the tritone is the key ingredient in a Dominant 7th chord. The notes of a G7 chord are G-B-D-F. The B -- F is a tritone.

Now, I say that this is ironic because Dominant chords provide a lot of motion in music. Certain chords like a minor or Major chord may or may not evoke a feeling of "I need to move to another chord!" You might end on a Major or minor and the ear would be perfectly happy if you stay there. Whereas, a dominant chord wants to resolve to another chord.

Well, let's think about resolution in the "real" world for a minute. When there is a conflict, a resolution needs to be made. That resolution might lead to a "typical" response or a "deceptive" response.

If you are caught littering, the "typical" response might be a fine. The "deceptive" or "atypical" response might mean that you have to walk around picking up trash for the day. We are accustomed to typical responses in our everyday life. You say something mean and someone gets mad at you. But what about when that person confronts you gently and asks "Why were you so mean to me?" That (unfortunately) is more of an atypical response.

O.K., back to music. Just like in "real life" we have typical and atypical responses or "resolutions", we also have these types of resolutions in music.

Certain chords want to naturally move to other certain chords. The dominant 7th chord is a prime example of this.

The typical resolution for a dominant 7th chord is to resolve down a 5th (up a 4th) to a Major or minor chord.

Some examples:

G7 resolves to C Major or minor

D7 resolves to G Major or minor

F7 resolves to Bb Major or minor, and so on...

You might be asking "What about the Blues chords? They don't resolve as they 'should.'"

In the Blues, the dominant 7th chords do not resolve as they "should". It is one of the reasons that the Blues has such a unique sound.

When a dominant 7th chord does not resolve as it normally should (down a 5th) we call this deceptive resolution. There is an exception to this rule that I'll get to later.

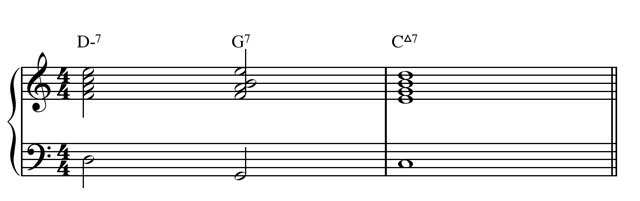

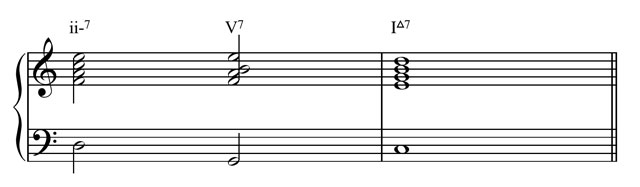

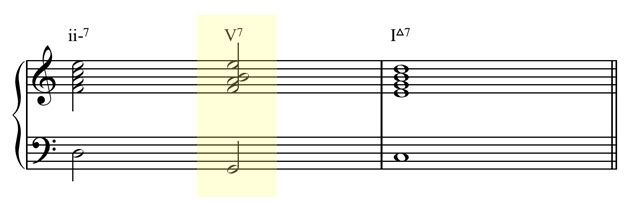

It is easy to see dominant motion in action using the ii-V-I progression. This progression is very common in jazz and popular music. Example 1 & 2 show a basic ii-V-I example in the key of C.

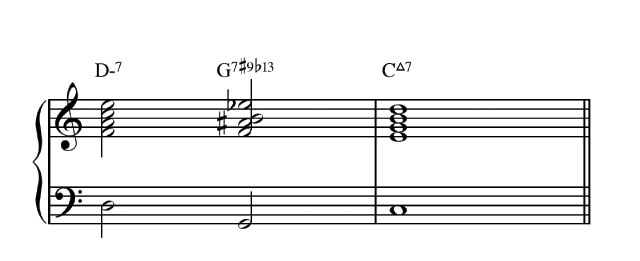

Ex. 1

with the "analysis" written in...

Ex. 2

So, our dominant motion is when the V7 chord resolves to the I chord (in this case a Major 7 chord).

Ex. 3

To use a tritone in a ii-V-I, first start by finding the tritone of the V7 chord's root. Yikes! That's a mouthful. Let me break it down for you:

- What is the V7 chord? [It is G7]

- What is the root of G7? [It is G]

- What is a tritone (higher or lower...it's the same note) of G? [The tritone is Db]

To find the tritone easier, first find the 5th (D), then go down a 1/2 step (Db).

I think it is easier to think of it this way rather than sharping the 4th.

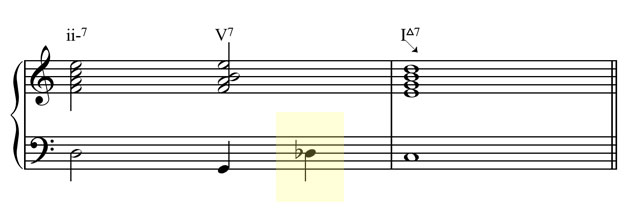

O.K., so we now know that the tritone of G is D flat. See example 4.

Ex. 4

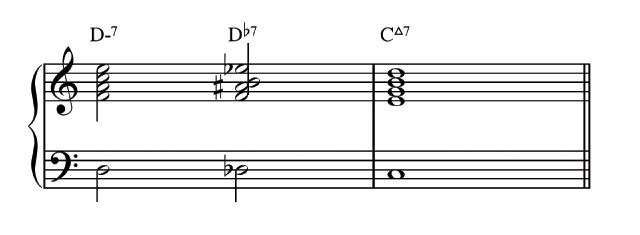

Next, replace the root of the G7 with the Db. DO NOT move the notes of the right hand, keep them the same. See example 5.

Ex. 5

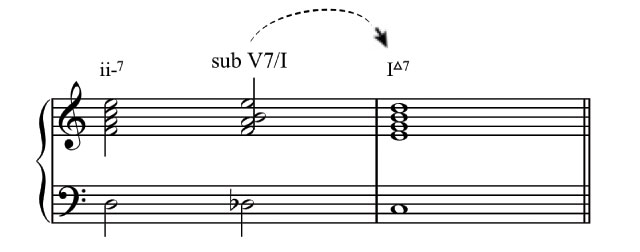

Let's pick this apart. First, do you notice how the analysis has changed from V7 to sub V7/I? This is because the V7 chord is no longer functioning as a regular "plain ol'" V7 chord. It is now a "sub" V7. This is just another way of saying that it is a tritone resolution. You would call this a "Sub Five Seven Of One." We call the '/' "of," not "slash."

Now, if we put the chord symbols back in we get example 6.

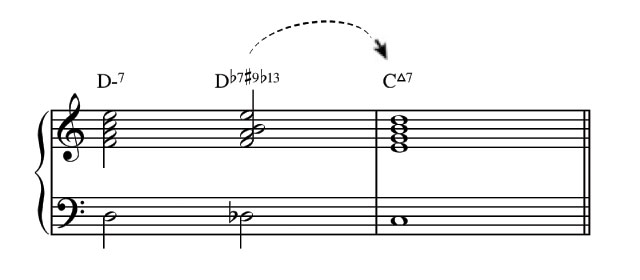

Ex. 6

You'll notice that the "regular" or "plain ol'" G7 chord has now become a Db7 chord with a #9 and b13. This is one hip-sounding chord!

In my series on Piano Chords, I cover these sub V7 chords and how to create them in more detail. I also show you how you can switch between the Dominant 7th and its tritone to create some interesting chords. Learn more about tri-tones and piano chords.

Here is an example.

Ex. 7

You'll notice that I have changed the G7 chord to a G7#9b13 chord. This is the same chord that I just created on Db when I changed the root of the "plain ol'" G7 chord to Db. Now, look at what happens when I change this altered G7 chord root to a Db:

Ex. 8

Do you see how now the altered G7 chord sound creates a "plain ol'" Db7 chord. Interesting huh? This is a nice way of creating an altered sounding chord. By altered sounding, I mean the tensions are not just 9 or 13, but altered to be a b9, #9 or b13.