Tritone Substitution - Part 1 of 2

The tritone is a very common device used in the jazz and Great American Songbook repertoire. It's responsible for some of those very interesting, authentic jazz harmony sounds that sets jazz apart from other genres. But although the tritone (also known as the tritone substitution) is common in jazz and cocktail music it is often seen as confusing and difficult to understand. And of course, if you don't understand something you're going to be hesitant to approach it or try to use it. In this article, we're going to clear up that confusion by explaining:

- What is the tritone and tritone substitution? and;

- How does it work (what is the theory behind it)?

What is a Tritone?

A tritone is actually an interval. That's right - a tritone is simply a specific distance between two notes, and in music we measure distance in terms of intervals. The tritone interval is another way of referring to an augmented 4th or diminished 5th. (An augmented 4th is really the same thing as a diminished 5th, just a different way to spell the same interval).

What is a Tritone Substitution?

This is where the confusion usually begins for students. A tritone substitution is the process of replacing one dominant 7th chord with another dominant 7th chord located a tritone away from the original. We're only talking about dominant 7th chords, not major or minor chords.

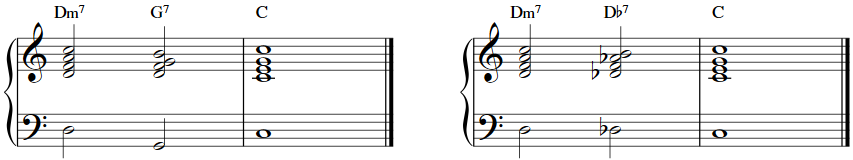

So let's plug in some variables. Consider a "ii-V-I" progression in the key of C major (Dmin7 - G7 - Cmaj7). We can substitute the G7 chord with a different dominant 7th chord. In order to know which dominant 7th chord we have to know the note that is a tritone away from G. In other words, what note is a diminished 5th (or augmented 4th) away from G? The answer is Db. So we can replace the G7 chord with a Db7 chord, resulting in a progression that reads Dmin7 - Db7 - Cmaj7.

How and Why Do Dominant Chords (and Tritone Substitutions) Work?

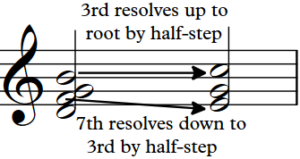

Keep in mind that dominant chords want to resolve to their 'I' chord. There is inherent musical tension inside a dominant chord that makes it feel unstable. Dominant chords have a musical pull to their 'I' chord. What gives it this pull? The guide tones (the 3rd and 7th of a chord) want to resolve by half step (called voice-leading) in contrary motion. This half-step/contrary motion is some of the strongest resolution in music. Consider the G7 to C major chord progression below:

So the 3rd and 7th of the G7 chord are the two notes which are responsible for the function of a dominant chord. Those are the notes which pull the dominant chord to their resolution on the 'I' chord. Notice anything that the G7 and Db7 chord have in common? That's right, the 3rd and 7th are the same in both chords (B and F = 3rd/7th of G7, 7th/3rd of Db7). And since the guide tones are the same, the inherent tension functions in the same way, allowing both the G7 and Db7 to pull to the C major chord in the same manner.

Nice review of why the V7 works that way. Looks like the IIb7 alternative adds some extra tension and also the cool walk-down in the base from II to I.

Thanks Derek, appreciate that! Yeah, this is cool stuff for sure.

very lucid explanation of a tricky concept but once I sat down at the piano and worked through the patterns, the sounds rang true...

Did the Trifone substitution come about B/O of theory or was it discovered via trial and error, historically?

I may have read in your Part 2 or elsewhere, that tritone substitution is often done for every other chord, such that for the original progression Em7 A7 Dm7 G7 C, for example, we would play the progression Em7 Eb7 Dm7 Db7 C instead, thereby creating a descending bassline E Eb D Db C, or some concept to similar effect.